Startups and shame

How founders overcome the silent shackles digging at them

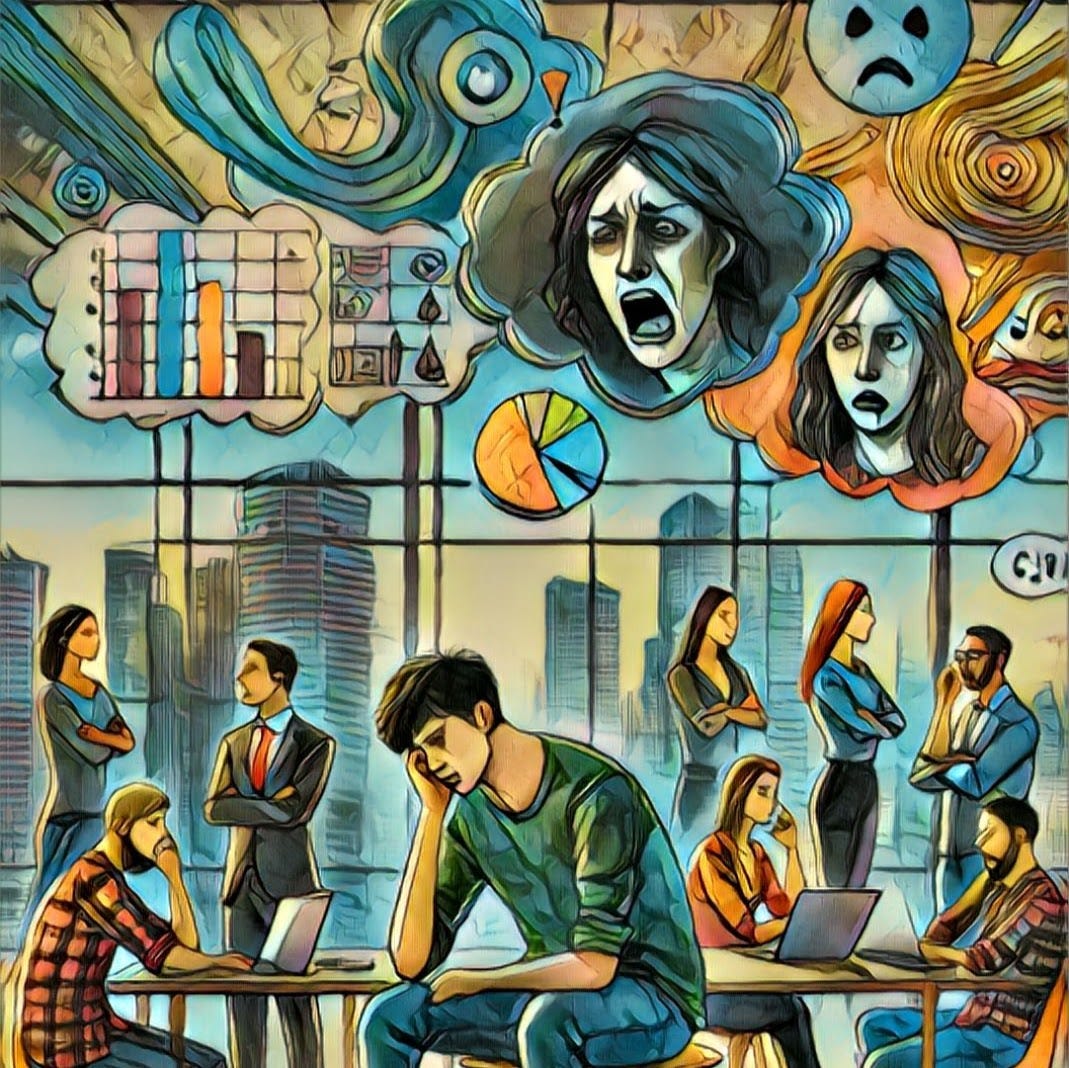

More times in my work life than I want to admit, shame held me back — held me back from seeing what I could do, or from admitting the full truth of what was happening. When it comes to talking about your mental health, shame is the emperor emotion. Shame commands other emotions, warping your thoughts and actions, without you even being aware it’s sitting on the throne.

As a VC, I see founders struggling with shame — and investors making it worse. (Of course I wanted to share examples of founders suffering from this — and a couple of founders I asked said they’d rather keep it off the page, even anonymously, which shows how hard it is to talk about shame!)

If we understand shame better, together, maybe founders will suffer less and their startups will more easily realize their potential.

Sadly, startups manufacture shame. Many founders are Type A “I always win” people who believe they can overcome any obstacle. In their startup, they walk an unmapped road, where the odds of reaching their destination are long. In startups, it’s hard to tell if you’re succeeding, and that success depends on the opinion of others. The fear of experiencing shame often fuels founders, for better and worse.

For founders who are “pleasers,” they’re signing up for an impossible-to-win game. Even in successful startups, someone is always unhappy with you. (Your new $10M customer? They’re furious you sold the same service to their competitor.)

Founders often feel a whole array of “shoulds”: I should know how to negotiate this deal, I should be able to recruit this executive, I should be able to fix this bug. Life isn’t like that, and startup life less so. Founders think they can do everything, and then reality punches them in the mouth.

Founders also sometimes lack self-understanding — otherwise, they might not be the kind of person to do the irrational and start a company! The kinds of people who start companies are exactly the people who suffer from shame.* Then, the accumulated stress of startup life — burnout — adds its own shame, about the exhaustion itself. “If I were stronger, I could just do this.” Even superhumans have limits.

Spending time with other founders can deflate a founder even more. Founders should be a source of support, but can often start a conversation with “what’s your ARR?” The shame groove digs deeper.

In almost every startup, at some point, something outlandish happens. Even abnormal challenges (like lawsuits, betrayal by close friends, threats to expose personal secrets, theft of company intellectual property, and more) are a frequent part of startup life.

Then, investors make it worse. They move the bar, because startup success might literally involve creating one of the best-performing companies in the history of capitalism. So, an investor will rarely say “you got an A+,” and often they’ll say much worse. (In my own startup, an investor canceled a signed term sheet on us the Wednesday night before Thanksgiving, with only two weeks of cash left in the bank. I was ashamed to even tell my family, but they saw it on my face.) As an investor, I’ve been guilty of making things worse, too.

Founders sometimes see their investors as authority figures (when, in principle, we’re just vendors of capital) and relationships can get dicey: treat your investor as a surrogate parent, and whatever issues you had as a kid can show up in the boardroom. Founders who want to win the approval of their investors (which can be valuable and, in some cases, essential) will often start to think of themselves as employees who work for the investor.

Some investors take advantage of a founder’s willingness to see them as an authority, to exert influence or control. Some investors play nice before the investment closes, only to reveal that they actually want to throw their weight around. Or they think they’re helping, and sound patronizing (which can often happen with founders from underrepresented backgrounds).

When an older, wealthier person who has a fancy office and a fancy title tells you to do things, it’s hard to remember that that person — the VC — should be there to serve you. (I’ve even had founders tell me they were afraid of being fired, because an investor told them they were pushing them out — when the founder had majority control of the board and so there was no chance the investor could push them out.)

Shame damages. Founders who feel shame might harm themselves. They might turn away from friends and colleagues, losing the support of their community. They might lash out, acting in unpredictable, hurtful ways to protect their self-esteem. They might turn to alcohol or other addictions.

Founders who feel shame might also lead their startup astray. Startups thrive on unearthing important truths, acting on those truths quickly. Shame clouds truth. Founders might miss facts that would prompt them to correct course, because admitting those facts (even to themselves) might be embarrassing. Founders might actively conceal important facts from their team, thinking they are keeping them confident, or from investors. A founder feeling ashamed might even falsify financial documents and commit a crime.

In less extreme cases, ashamed founders stick to a losing plan for longer than they should. They keep an underperforming executive, or one who’s a bad actor, because they bragged to their investors about the new hire with the glittering resume. Founders might surround themselves with “yes people” who affirm their sense of self, without moving the startup in a winning direction. It can all spiral.

How can we support founders facing shame? First, investors (or co-founders, teammates, and friends) need to try to spot when a founder is feeling shame. That’s hard, because one of shame’s strategies is to hide the truth — even the person feeling it may not know.

The number one sign a founder is facing shame is when they withdraw — but it’s a tricky sign. When “the dogs stop barking” (i.e., a founder who sent an update every month like a clock stops sending them), get curious. Withdrawal can happen for many reasons other than shame (startup life gets busy!); so, if you notice something’s changed, just ask what’s going on.

Shame might show up differently depending on a founder’s personality, of course, and their age, gender, national origin, and more. We should attune to these nuances and adapt our approach to make every founder feel safe sharing the truth.

At Bloomberg Beta, we sometimes open the conversation with founders about their inner life before we even invest — to make clear that’s part of our support for them. Investors can ask if the founder understands their personal relationship with fear, guilt, and shame. (We even have a suggested way of asking founders about shame here, where we share our methods in public.)

Brené Brown has, for many, opened the “let’s talk about shame” door.** And, still, most people will never say “I’m ashamed,” let alone “I’m ashamed and I’m worried it’s clouding my professional judgment.”

Allies to founders should tell stories (with the consent of founders) about shame, how people feel it, how it affects their perspective and actions — because that will normalize talking about it, make it easier for others.

Founders can be particularly reticent to acknowledge these feelings (and the mistakes or challenges that triggered them). They worry that if they admit something went wrong (regardless of whether it’s their fault), the startup might spiral down. “If I tell the team how short our runway is, they might lose confidence.” Customers might lose confidence. Investors might lose confidence. And confidence is the oxygen of startups. Sometimes the right strategy is just to march onward.

If you’re a founder, the first step in defanging shame is to name it aloud — first to yourself, and then to someone you trust (when you’re ready).

Practice the habit of sharing the worst news you see, regularly, with the right people. (Of course, as investors, we hope founders will trust us — and we also know the investor relationship can be fraught. You can test out whether the investor is safe to share hard news with, by using the egg-toss approach to trust.) If you find yourself avoiding thinking about something you know is a real issue, catch yourself being defensive, or have zero people with whom you can share your deepest challenges, those are signs shame may be creeping up on you.

Cultivate some founders who you trust to keep your difficulties to themselves. Break through the wall of masks so you can skip trying to convince them everything is great. Other founders will understand your troubles better than anyone, and ideally there’s nothing you need from them. (When I was a CEO, we had a group that would meet at 7am for breakfast every so often, and I still talk to every member of that little group — and have invested in three of their companies! One is now a great coach who supports groups of founders while he works at Amazon.) Just be careful because some founders do gossip to try to elevate themselves with investors and talent and others.

If you’re an investor, recognize that the founder-investor relationship is fertile soil for shame.

Many investors struggle with their own shame! We might feel embarrassed that a startup turned out differently than we thought. At some firms, an investors’ own teammates might give them a hard time for making a particular investment. When we feel shame, we often redirect that feeling onto others in the form of harsh criticism. I’m sure I’ve done this, as an investor, speaking out at a founder or someone who works for them (as recently as last week!) — and I regret it. Taking accountability for your own actions is harder than blaming others! Ideally investors will support founders when the chips are down and remind you to treat yourself with compassion (though so few do).

When we investors sell money to a startup, we usually sign up to offer a range of services — customer introductions, advice with fundraising, and more. I believe investors also need to serve a founder’s mental health (though founders are adults who are ultimately responsible for themselves).

If I suspect a founder is in a shame spiral, I try to respond by reminding them why I support them, and try to shore up their confidence. Then I will just ask, simply, if there’s anything they’re worried about that they want to share. If they want to keep their demons private, I respect that.

Then I will offer that, if a founder is in a tough mental spot, we’re happy to offer resources to support them — a coach, or a therapist. I try to make clear that their inner life is important to us, because we serve the whole person. A good VC will have a roster of people ready to shore you up. When investors do this right, we can be a shock absorber, putting the hard times in perspective.

As investors, founders sometimes apologize to us for poor performance. My take is that, as long as the founder genuinely tried, made changes to adapt when things went sideways (as they always do), they owe no apologies. A baseball player doesn’t apologize for swinging and missing.

A tough truth about startups, which explains the personalities of some of the most successful founders of our time: startup life is emotionally grueling. (I sometimes quip that it’s easier to be a founder if you’re a sociopath. Sad but true.) If you’re a founder, keep trying to form a little team of non-judgmental support around you — even one or two people you can tell anything can make all the difference (especially if they’re founders who can relate). If you’re experiencing shame, and especially if it’s starting to spiral and you’re thinking dangerous thoughts, get help. If you don’t think you’re the kind of person who needs help, you may be exactly the person who does need help.

Remember, your worth as a person is unrelated to your startup’s performance. By learning to handle shame in a healthy way, you can unlock your startup’s potential, your power as a leader, and an easier life.

* Why do the kinds of people who start startups feel especially vulnerable to shame? Many startup founders are younger men in their 20’s and 30’s, who often suppress their own awareness of fear, guilt, and shame. As one founder said to me, “The people who build companies aren’t usually the type who have been in therapy.”

And female founders, especially parents, tell me they experience even more of the shame-pull of being torn between startup life and personal expectations. They describe being torn between the desire to prove they can do it and the difficulty of actually doing that. Kids may feel the paradox of pride and missing-my-parent pain with a busy parent of any gender; I know my kids saw my issues.

Let along all the ways that founders who are different from the stereotypical profile feel they need to overcome. We try to see you all.

Post Comment